Game On: The Rise of Esports in Oklahoma Schools

Story by Charles Gerian | Staff Writer

➡️ This article is one of the FREE preview articles included with our free membership option, we hope you enjoy this free content!

➡️ Do you love reading stories from Ponca City Monthly? Don’t miss a single article, sign up for our email newsletter and get them delivered directly to your inbox. You can subscribe here.

For generations, ambition for college-bound students followed a familiar script: lace up cleats, polish a trumpet, join the choir, take center stage on the court or the field.

These were the golden tickets—the résumé-builders that caught the eyes of scholarship committees and admissions offices. Parents and teachers encouraged it, telling their kids that sports and music weren’t just pastimes, they were stepping stones to a brighter future.

But for just as long, another pastime was pushed aside. “Put down the controller,” kids were told. “Pause the game. Go do something productive.” Gaming was seen as a distraction, a hobby best left in the basement.

Now the script has flipped. In a digital age where competition takes place on glowing screens instead of grassy fields, young people are finding real opportunities in the very activity adults once dismissed as a waste of time. Professional streamers build entire careers on YouTube and Twitch. College recruiters now scout talented gamers with the same seriousness once reserved for quarterbacks or point guards. In 2020 alone, more than $16 million in esports scholarships were awarded across the country.

Oklahoma is no stranger to this shift. The Oklahoma Secondary School Activities Association has officially recognized esports, with high schools statewide fielding teams through PlayVS, a sanctioned partner helping to organize competitions nationwide. Just as students can go out for football, baseball, wrestling or softball, they can now represent their schools in titles as varied as Street Fighter, Overwatch 2 and Mario Kart.

It’s not a trend anymore—it’s an institution in the making. And right here in Kay County, the movement is already reshaping how students, parents and educators think about competition, teamwork and the future.

When Ponca City High School opened its new STEM building in 2024, students gained more than classrooms filled with technology. They also gained an arena—one without bleachers, but with rows of computers, consoles and headsets. It was here that Ponca City launched its esports program, an idea championed by Superintendent Adam Leaming and one that has quickly become a home for students who want to compete on a different kind of playing field.

At the center of it is coach Ian Rand, a lifelong gamer who wishes he’d had the same opportunity when he was in high school. “I wanted to coach esports because I play several of the video games, and I wished I could have been on a high school esports team when I was in high school,” he said. Now, he’s the one helping students turn their hobby into a team sport—and in some cases, into a path for their futures.

Explaining esports to skeptics is one of Rand’s favorite challenges. “Esports are competitive video games played against other high schools in the state of Oklahoma,” he said. “They’re more than just playing video games because it requires communication with team members, self-reflection, discipline and good sportsmanship.”

Ponca City’s team competes in Overwatch 2, Marvel Rivals, Super Smash Bros. Ultimate, Rocket League, Fortnite and Apex Legends—games chosen by the students themselves. Rand said the program has grown rapidly, and not just in numbers. “The biggest growth is how our student gamers communicate with their teammates,” he said. “When they started, they were only used to playing by themselves and had no communication. Now they’re able to talk, give callouts and cooperate, all while playing their video game.”

The team’s roster is as varied as the games themselves. Students come from different grade levels, skill sets and interests, with some also involved in football, band, yearbook or other school activities. “All sorts of students are drawn to esports,” Rand said. “It gives them a place to belong.” He has seen players gain confidence that carries into other parts of their lives, and especially into leadership roles. “Their teamwork and leadership have grown, especially in the team captains as they have to lead their teams in the games.”

A typical match day at Po-Hi depends on the format. Most competitions are virtual, with students gathering an hour early in the esports room to practice before facing another school online. Coaches then report scores on the league website. But there are also travel days, where the Wildcats pack up their consoles and controllers, load the bus and set up at another school to compete in person.

Preparation goes beyond practice matches. Players review their own game footage, study professional esports players and drill strategies specific to their chosen titles. And when the stakes are high—such as the in-person state tournaments—the atmosphere rivals any traditional sport. “The energy of a live esports competition is crazy,” Rand said. “Coaches, other players, parents and other spectators cheer and yell for their teams.”

The Wildcats have already carved out rivalries, with Bixby standing as their biggest competitor. A highlight for the team came when Ponca City toppled Bixby in Overwatch 2, a win that Rand still remembers with pride.

The success isn’t limited to competition, either. One senior recently earned an esports scholarship to Cowley College, while another went to the University of Oklahoma to work as a video editor for the OU esports team. For Rand, those opportunities prove the legitimacy of the program. “Life skills that students take away from esports are communication and self-reflection,” he said. “Academics are still the priority, and when students are ineligible, they know practice comes second to homework. But esports can open doors.”

Rand also wants to change the way people perceive esports. “One stereotype I wish I could change is that it’s just playing video games,” he said. “These video games are some of the most difficult games to play. To add to that, the whole team has to communicate, remember in-game locations and abilities, and time their abilities for the best plays.”

Even with the serious side, there are lighter moments that keep things fun. Rand laughs about practices where his team is suddenly matched against some of the top 500 players in the nation—a nerve-wracking but exciting challenge. And despite the intensity, the moments that make him most proud aren’t always victories. “The moments I am most proud of as a coach are when I see my student gamers talking and hanging out with each other outside of esports practice,” he said. “I am proud that they are making friends and are engaged in bettering themselves outside of esports.”

Looking ahead, Rand believes the future of high school esports is only going to grow. With esports now recognized by the Olympics and colleges across the country offering scholarships, he sees opportunities expanding rapidly. “In the next five years, I see high school esports growing to amazing levels,” he said.

At Ponca City High School, that growth is already underway—one match, one team and one headset at a time.

When you walk into the Blackwell Middle School esports room on match day, the energy feels familiar, even if the arena looks different. Instead of a gym floor or a football field, the battleground is a row of glowing monitors, and the roar of the crowd comes from teammates huddled close, calling out plays with headsets on. For Coach Amber Dunham, that scene is the culmination of a vision that began with a grant proposal and has since grown into one of the school’s most exciting programs.

“We put together an OTTE grant proposal through the K12 Foundation at the University of Oklahoma to secure the equipment we needed,” Dunham explained. “The whole process involved clearly outlining what we needed, why it was crucial for our project, and how it would make a significant impact.” That impact has been felt quickly. What started with a handful of curious gamers has grown into a competitive program with more than 20 students and even an expansion into Blackwell High School in just four years.

For Dunham, the motivation to coach was about more than just games. “It was a way to reach different groups of kids that aren’t necessarily in the spotlight,” she said. “It allowed them to create a specialized community within our school, foster communication skills and encourage students to keep up their grades. Plus, it just seemed like a fun way to connect with students in this generation.”

Esports, she insists, are anything but “just video games.” She calls them a mental battleground. “Unlike physical sports, where raw athleticism often takes the lead, this game demands quick thinking, sharp focus and the ability to anticipate moves in real time. Every call counts, and the mental endurance required is unlike anything you’d find in a typical physical sport.”

The Blackwell teams compete in the Oklahoma Scholastic Esports League, with students choosing from titles like Rocket League, Halo, Fortnite and Pokémon Unite. Dunham builds the teams based on student interest and skill, while her assistant coach, Chad, and IT support, John, help manage the logistics of competition. Match days look different depending on the format: monthly core games with three-round matches against assigned opponents or weekly virtual contests that connect Blackwell to schools across the state. Some events are streamed, and plans are underway to add shoutcasters to give broadcasts the same energy as professional tournaments.

Behind those matches is plenty of preparation. In addition to after-school practices, Blackwell students train in a dedicated esports class that emphasizes communication, strategy and self-improvement. They watch recordings of their matches, study professional players and refine their gameplay in warmups and scrimmages. And while every competition brings intensity, the state tournaments carry a special electricity. “Anytime we qualify for state, the energy is absolutely infectious,” Dunham said.

The program has already made its mark at the state level. A thrilling comeback victory in Halo against Canute secured a championship for Blackwell, and the Maroons have also claimed a title in Valorant and runner-up finishes in Overwatch, Fortnite, Pokémon Unite and Mario Kart. The rivalry with Canute, whose coach also happens to run the OKSE League, has become one of the highlights of the season. “It’s competitive, yet respectful,” Dunham said. “Our teams push each other to be better.”

But the real rewards, she insists, go beyond trophies. Dunham has seen quiet students become vocal leaders, taking command during high-pressure moments and learning to analyze their play afterward. She’s watched students who once kept to themselves now build friendships that extend well beyond the esports room. “It’s incredible to watch them become more active and engaged in their daily school life,” she said. “They step out of their comfort zones, take on leadership roles and show a confidence that maybe wasn’t there before.”

That growth has become one of the program’s defining strengths. Students learn accountability by balancing academics with competition—grades come first, and struggling players are supported before being allowed back in the game. They also practice skills that translate far beyond gaming: time management, teamwork, problem-solving and resilience. “They’re learning real-life skills that carry over into school, work and everyday situations,” Dunham said. “And it all starts with something they enjoy.”

The culture of the team is rich with traditions, both serious and silly. Players have pregame rituals, from music playlists to lucky gear. Their unofficial theme song has become the Backstreet Boys’ “I Want It That Way,” after one student’s impromptu performance turned into a full-team singalong. And between matches, the students once entertained themselves by sliding down the hallway in their socks, “skiing” as Dunham laughingly recalls, to burn off nervous energy.

Looking to the future, Dunham believes the growth of esports in Oklahoma is only just beginning. When Blackwell first joined the OKSE league, about 50 schools were involved. Today, that number has passed 200, with more joining each year. Colleges are offering scholarships, and career pathways in gaming—from media production to event management—are opening up. “I think high school esports is going to keep expanding,” Dunham said. “And I expect to see more schools in our Kay County area getting involved as the scene continues to grow.”

For now, the Blackwell Middle School esports team is proving that competition doesn’t have to take place on a field or a court to change lives. It can happen on a screen, headset on, with teammates leaning forward in the glow of the monitors, learning lessons that will last long after the final match ends.

When Pioneer Technology Center in Ponca City launched its esports program in 2021, it was little more than an experiment. Administrators had seen the rise of competitive gaming in education and asked IT instructor Zac Ladner to explore whether it could work at PTC. With little experience in gaming himself, Ladner leaned on his students to help host a trial run: a campuswide Super Smash Bros. tournament. The event was a success, proving that esports could find a home at Pioneer Tech.

“From that proof of concept, it just grew,” Ladner said. “We went from one tournament to playing well over a dozen different games in the Oklahoma Scholastic Esports League.”

Today, just four years later, the program has blossomed into one of PTC’s most unique student offerings. Participation has swelled from 18 players in its first year to more than 45 this fall, so many that the school had to hold tryouts for starting spots. For Ladner, who never considered himself a gamer before stepping into the role, the journey has been eye-opening.

“I just kind of fell into coaching the team,” he admitted. “At first, I didn’t really understand it. But once I started playing the games myself and saw what it did for the kids, it clicked.”

For outsiders who dismiss esports as “just playing video games,” Ladner has an answer. He points to a graphic he often shows parents and administrators—a chart mapping the many careers tied to the industry. “On the surface you see kids with controllers,” he said. “But really, it’s teamwork, communication, problem solving, strategy, leadership. And behind the scenes, there are roles in IT, production, broadcasting, marketing. It’s no different than any other sport when it comes to preparing kids for the future.”

The games themselves range widely, with students choosing from whatever the league offers each semester. This fall, the PTC roster includes Marvel Rivals, Rocket League, Fortnite, Call of Duty: Black Ops 6, Apex Legends, Street Fighter 6, Tekken 8, Guilty Gear Strive, NCAA 26, NBA 2K25 and Smash Bros. It’s an eclectic lineup, reflecting the diversity of the players themselves.

And those players aren’t the typical faces you’d expect to see on a basketball court or football field. Many had never been part of a team before joining esports. For some, physical sports weren’t accessible; for others, traditional athletics simply didn’t spark their interest. “Esports give them that first chance to belong,” Ladner said. “It’s their community, their team. And once they get in, you see them start talking, start leading. It pushes them out of their comfort zones.”

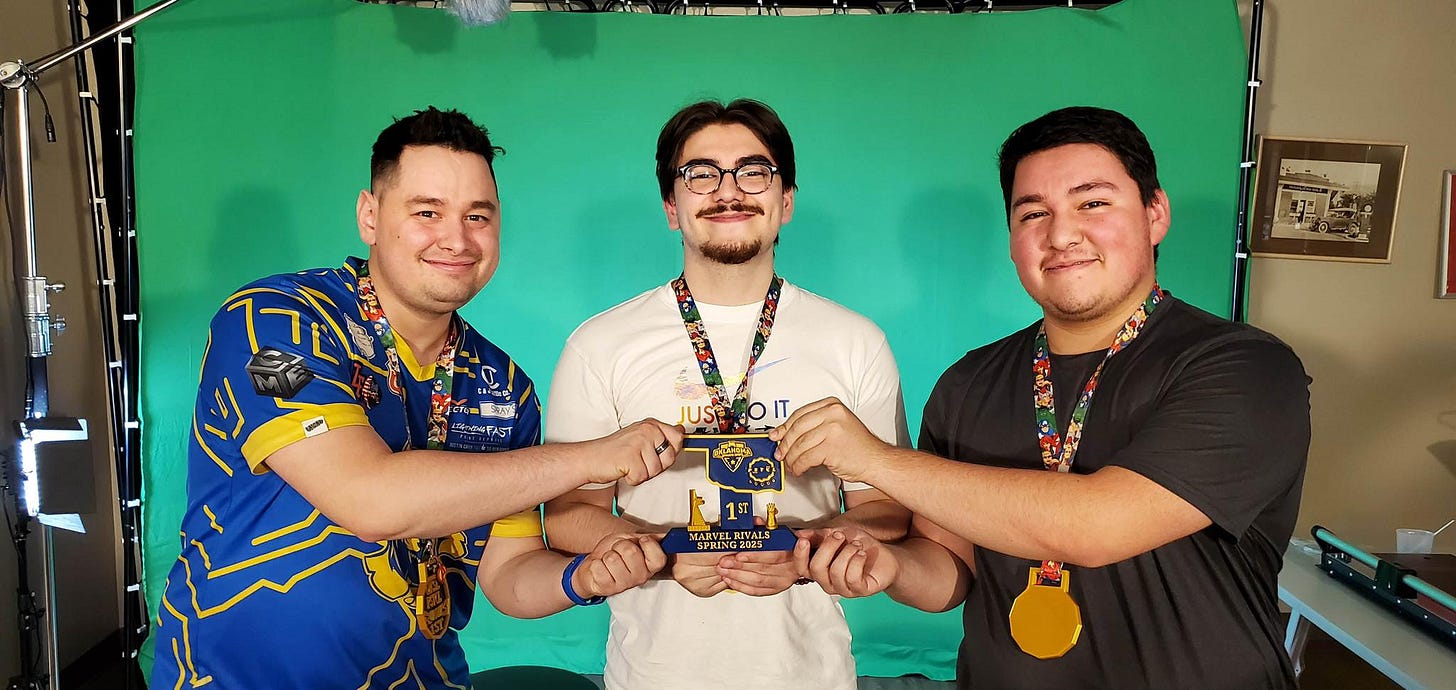

That growth is one of the coach’s proudest rewards. He recalled a student who once tried to disappear into the back of the classroom, quiet and unnoticed. “He told me he finally found confidence through competing,” Ladner said. “He ended up on our adult Marvel Rivals team, and they won the championship. That confidence spilled over into his schoolwork and his personal life. That’s the stuff that sticks with me.”

Live competitions bring their own energy—something Ladner compares to “a fourth-and-goal moment in football with the game on the line.” He described watching a practice duel between two students, one from high school and one from the adult league, who battled in Tekken. The match ended in a rare double knockout, and the entire room erupted. “You know a good game when you see one,” he laughed.

PTC has had its share of good games. One of the most memorable came last season, when the team fought its way out of the losers’ bracket in Marvel Rivals, defeating their opponents twice to win the championship. Rivalries have emerged, too, adding to the drama and fueling the students’ drive to improve.

Beyond the thrill of victory, the program emphasizes critical thinking, time management and communication. Matches are scheduled after school with set times at 4 and 5 p.m., and students often stay late in the esports room to practice. Thanks to a grant from the Oklahoma Educational Technology Trust, the program now boasts professional streaming equipment, broadcasting games live on Twitch and YouTube. This not only allows students to review their play but also opens doors to careers in production and digital media.

Of course, academics come first. Players must maintain eligibility both at PTC and at their sending schools to compete. When students struggle, Ladner steps in to help—even if it means brushing up on English homework, something he jokes is not his favorite. “Since esports started, I’ve been an everything teacher,” he said.

The players have embraced the identity of their team, even crafting a mascot: Petey the Manticore, a mythical mashup combining pieces of the sending schools’ mascots. Ponca, Woodland and Newkirk each contributed their feline imagery; Tonkawa brought in its Buccaneer roots; and Blackwell’s Spirit of the Maroon rounded out the design. Petey now stands as the guardian of PTC esports, complete with a fight song that, fittingly, was drafted with the help of artificial intelligence.

As Ladner looks ahead, he sees nothing but growth. Colleges are adding programs, scholarships are expanding and the industry itself is booming, generating billions annually worldwide. Several of his players have already attracted college offers, though none have signed yet. “It’s just going to get bigger and bigger,” he said. “Esports are here to stay.”

And though some may still dismiss it as screen time, Ladner insists the truth is clear to anyone who steps into the esports room on match day. “Until you see it in action, you just don’t get it,” he said. “I didn’t. But once you do, you realize it’s the same as Friday night lights. It’s kids competing, learning, growing—and finding a place where they belong.”

➡️ Opt in or out of different newsletters on your “My Account” page.

➡️ Learn more about Ponca City Monthly+

Ponca City Monthly is a locally owned media company that delivers hyperlocal news through in print and online.

Like what we are doing? Feel free to forward this along and tell a friend.

Sponsorship information/customer service: email editor@poncacitymonthly.com